Story and photos by Sharon King Hoge

Siberia may be notorious for hard labor in harsh winters, but traversing Russia by train is a pleasant fascinating trip. The passing landscape outside may be swampy and mosquito infested in summer or bleak and frozen in winter, but viewed from on board, the scenery is dotted with villages of wooden houses, endless birch trees, and occasional stops at pastel depots. Passengers are friendly despite language restrictions, and the efficient staff keeps the cars spotless with daily scrubbing and vacuuming. A full seven days and six nights after leaving Moscow on the famous Rossiya train, I landed in Vladivostok almost 6000 miles away departing my comfortable cabin with regret.

Siberian landscape from the window of the train

Various local trains cover the distance, but the principle long-haul train offers two optional routes. Last year I followed the southern path, Moscow to Beijing, interchanging with local trains so I could get on and off to explore Ekaterinberg, Irkutz, and Lake Baikal, disembarking early in Mongolia. The landscape had been green and forested in summer, and I was curious to see legendary frozen Siberia, so this March I chose the classic route, the Rossiya #2 which departs Moscow heading east for a week until it reaches Vladivostok. (The west-bound return trip, the #1, leaves Vladivostok on even numbered days). There is a luxury train that runs the route offeringcomfort, convenience, coddling, and stops along the way but it takes twice as long and costs multiples more than the $900 I paid for a first class ticket.

Engine on our Rossiya #2 Trans Siberian train

Wagon 7 stopped at a depot

Of the three classes of train service, I have tried out two. Third class, platzkart, is a kind of dorm, a car lined floor to ceiling with bunk beds; for such a long trip I didn’t even consider that. Basic tourist service kupe is closed compartments with four bunks which convert to seats for daytime riding. That worked for me last summer and during the course of that trip I shared the space with a range of fellow passengers intermittently assigned to my same chamber — businessmen, couples en route to visit relatives, and a grandmother/grade school age granddaughter duo. This time I splurged and booked spalny vagon i.e. first class. Each compartment has two lower convertible bunks situated on either side of a window table. If you’re not traveling with a companion, the railway assigns the companion space. Spotless bathroom facilities are shared, two compartments with toilet and sink situated at the far end of the car.Travelers fluent in Russian can purchase tickets on the web, and I tried, but grappling with the Cyrillic alphabet confounded me, and I turned to Art Sokol of Sokol Tours to line me up. Purchase can also be puzzling — both the web and Art’s agent reported that the train was almost fully booked, but for most of the winter trip there were fewer than half a dozen people in my wagon’s double compartments.

The trains depart at midnight from one of three adjacent stations in Moscow’s “railway” neighborhood around the Komsolmoskaya metro stop. I located my assigned place — Wagon 7, Compartment 2, Bed 4 and met Vera, the “stewardess” or provodnitsa, who would oversee and clean the car throughout the entire trip, employing her Russian/English dictionary when she needed to communicate with me. Impeccable bedding and two supersize pillows were laid out on my assigned berth along with a packet of slippers and amenities. I stashed my luggage below the bed and spread out the fluffy duvet. Since it was pitch dark and I’d had a busy Sunday sightseeing through the Kremlin I fell promptly to sleep.

My compartment Wagon 7, Compartment 2, Bed 4

Corridor of Wagon 7

Awakening the next morning I watched snowy fields flashing by as I ate fruit, juice, and Danish I had brought along. My first class ticket included not one meal a day, but one meal (!!!) for six days—a bizarre option that may be offered as a loss leader to introduce the cuisine available from the dining car. The first noon, a tray with a delicious creamy chicken cutlet plus assorted cold cuts and a slice of cake was delivered by the very comely woman who served all week as a runner delivering menus and meals through the cars for those who chose to eat in their compartments.

Snowy scene Monday morning

Complimentary meal served in my compartment

The dining car is open throughout the trip. The trains I took in the summer served caviar salads in settings of sumptuous draperies and white table clothes. This time the dining car was fitted out with plastic booths, and though the one meal I had there was delicious (priced in the $10-$20 range) and served with beer and cognac options, I preferred to concoct meals from foods I bought along the way.

Cutlet preparation in the dining car

Jovial group in the dining car

Every few hours when the train would make a 15-30 minute stop at a station, I’d get out to explore. Vera would don her official uniform and stand at the steps using her fingers to show me how many minutes I had to explore before she would be pulling up the steps and closing the door. I’d set my stop watch and jump off to browse at the local trackside stands stocked with souvenirs and typical fare: breads, cheese, sausage, “pizzas,” and an endless choice of water, energy drinks, sodas — and, Snickers bars and chocolate. The staple offering is ramen noodles and other add-boiling-water food cups, which could be constituted with the constant supply of hot water in the samovar installed at the end of each railway car. When we were lucky, the train would be met by local vendors with coolers and baskets selling home-cooked foods — potatoes, cabbage salads, pirogis — and in some locations selections of delicious dried fish (notably Lake Baikal’s unique specialty omul whitefish).

Track side snack stand

Smoked fish supper

A few times there would be a “supermarket” close enough to the depot and I could run in and stock up on fruit, yogurt, bread, cheese — which Vera graciously stored in the tiny fridge in her compartment. And Vera was also a backup — if I missed a stop, I could choose from a variety of items she had on sale and she would deliver “room service” tea or cappuccino whenever requested.

Tea served by the provodnitsa

Vera, provodnitsa of Wagon 7

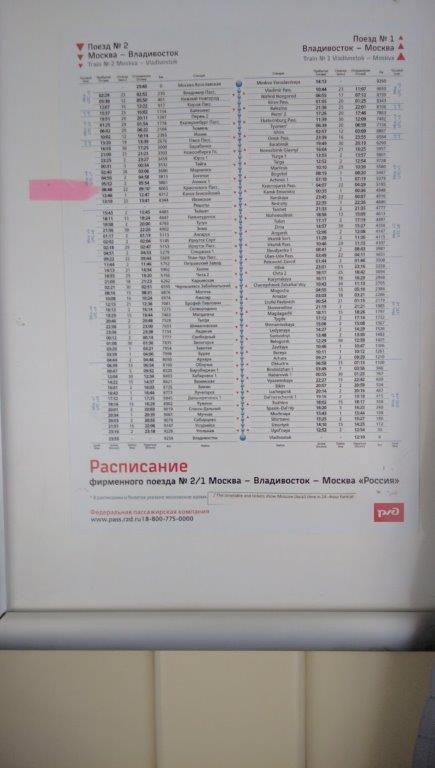

One of the railway’s quirks is the timing. Although we crossed multiple time zones and gained seven hours, the railway runs on Moscow time throughout. That means the clock may say it’s mid afternoon when out the window it’s the dead of night. If you want to know what time it is in the outside world, you have to study the timetable and add the correct number of hours to the Moscow time. Throughout the entire seven days the train ran exactly on schedule to the minute, landing at Vladivostok at 23:55 – midnight — although since we were seven time zones ahead of Moscow, it was actually 7 o’clock in the morning.

Time table on the wall

Different passengers make different choices – to go with the clock or to follow the sun. Eventually I worked out a routine of setting my cellphone alarm to wake me up for every stop night and day. Since I don’t expect to repeat the trip I wanted to see as much as possible—and sleep I missed I could recover by dozing off and on through the day. Possibly as an outcome, without having converted to a strict alternative set time schedule I found I barely had to deal with jet lag on my return.

Although guidebooks predict that by the third or fourth day passengers are apt to get stir crazy, I was never bored. The scenery varied from broad meadows to patchy forest to high hills and mountains. Frequently we passed villages of wooden houses hunkered in. While some of the depots have been modernized, many of them are neo-classical structures painted charming pastel shades and often enhanced with interesting monuments and statues. One glorious sparking sunny morning we followed along the south shore of the world’s largest lake Baikal –big enough to contain the water of all the American great lakes combined.

Summertime swamps flecked with winter snow

Typical landscape with birch trees

Depot at Yerofei-Pavlovich with dragon decoration

Misty view of world’s biggest Lake Baikal

A sunset view

There was a television set in my cabin, but the choices were limited – American vintage films “Spartacus” and the Taylor/Burton “Cleopatra” were on an all-day continuous loop – but translated into Russian. Much of the time I was engrossed in reading about the cruel, lascivious, conniving, ineffectual czars in Simon Sebag Montefiore’s juicy history of the Romanov family. And every day I would follow along the Trans-Siberian guidebooks. Both Lonely Planet and Bryn Thomas’s classic Handbook chronicle the route, describing towns and sites the train is passing so you can note when you’re crossing the highest point of the Ural Mountains or look out for the town named for the composer Tchaikovsky.

My compartment during the day

A constant lure is trying to read the kilometer signs. Theoretically every one of the 9289 kilometers along the route is marked with a signpost indicating the exact distance the train has traveled from Moscow. These are set close to the track on the south side, but in order to see them you have to squeeze up close to the window and keep close watch. Unless the train has slowed down, they flash right by. Even trickier was trying to snap a photo.

A kilometer signpost – near the once secret space center city of Zelenogorsk

Most of the time I could update emails. I had purchased a Russian sim card and had more or less constant cellphone service except during a few remote stretches when I’d have to catch messages as we passed through a town where there would be a signal.

For six hours, from Irkutsk to Ulan-Ude I was joined by Daria, an attractive young Russian woman traveling on business for Colgate Palmolive. She spoke a bit of English and we had some time to converse. The only other English speakers, a couple from London, joined me one night for a dining car dinner. Passionate travelers, they had worked on barges in France and were on the way to visit the family of their traveling companion who had grown up in Taiwan.

Daria, my compartment companion

Just when I was well adapted to my routine, the trip came to an end. Vera woke me up Sunday morning so I’d be ready to get off in Vladivostok. There were many hugs and fond goodbyes. The flight back to Moscow took nine hours — much quicker than the train but not nearly as memorable and pleasant.